Participatory historical geography

I am a scholar, writer, and geographer working with communities to make our past meaningful in the present, and intervening to preserve our past on behalf of our future. Over decades of research, collaboration, and publishing I have developed expertise particularly in the areas of ghost towns, the “Ramona Myth” in southern California, and how neon signs transformed the American landscape and shape our communities.

Dydia DeLyser: scholar, writer, Geographer

Landscape and social memory

My research and approach to understanding the world around us are grounded in the traditions of cultural geography, particularly that of interpreting ordinary landscapes. Here my chief interest is in social memory—how the past is made meaningful in the present.

I’ve explored that in different parts of California and the American West, including (here, at left) in the gold-mining ghost town of Bodie where abandoned buildings, preserved in a state of “arrested decay” (they’re kept standing but allowed to keep looking like they’re falling down) encourage visitors to imagine what life might have been like in the “rough and rowdy” says of Bodie’s 19th-century boom and subsequent bust.

I worked in Bodie State Historic Park for ten summers arresting decay and cleaning public toilets. I’ve been a volunteer there (doing the same work) for more than twenty-five years. As president of the Bodie Foundation I help raise money for stabilization, and share my research insights about the importance of Bodie’s model of preservation with staff and the public.

Scroll down for detail on this work, and for more examples of my other projects.

DYDIA DELYSER: SCHOLAR, WRITER, GEOGRAPHER

Ordinary landscapes create meaningful memories

People do important things in ordinary places. There we create memories that begin as individual and personal. Because we all live our lives in cultural contexts, we then link those memories to broader cultural ideas and social memories, connecting us to people who came before us, and to important themes in “American” identity.

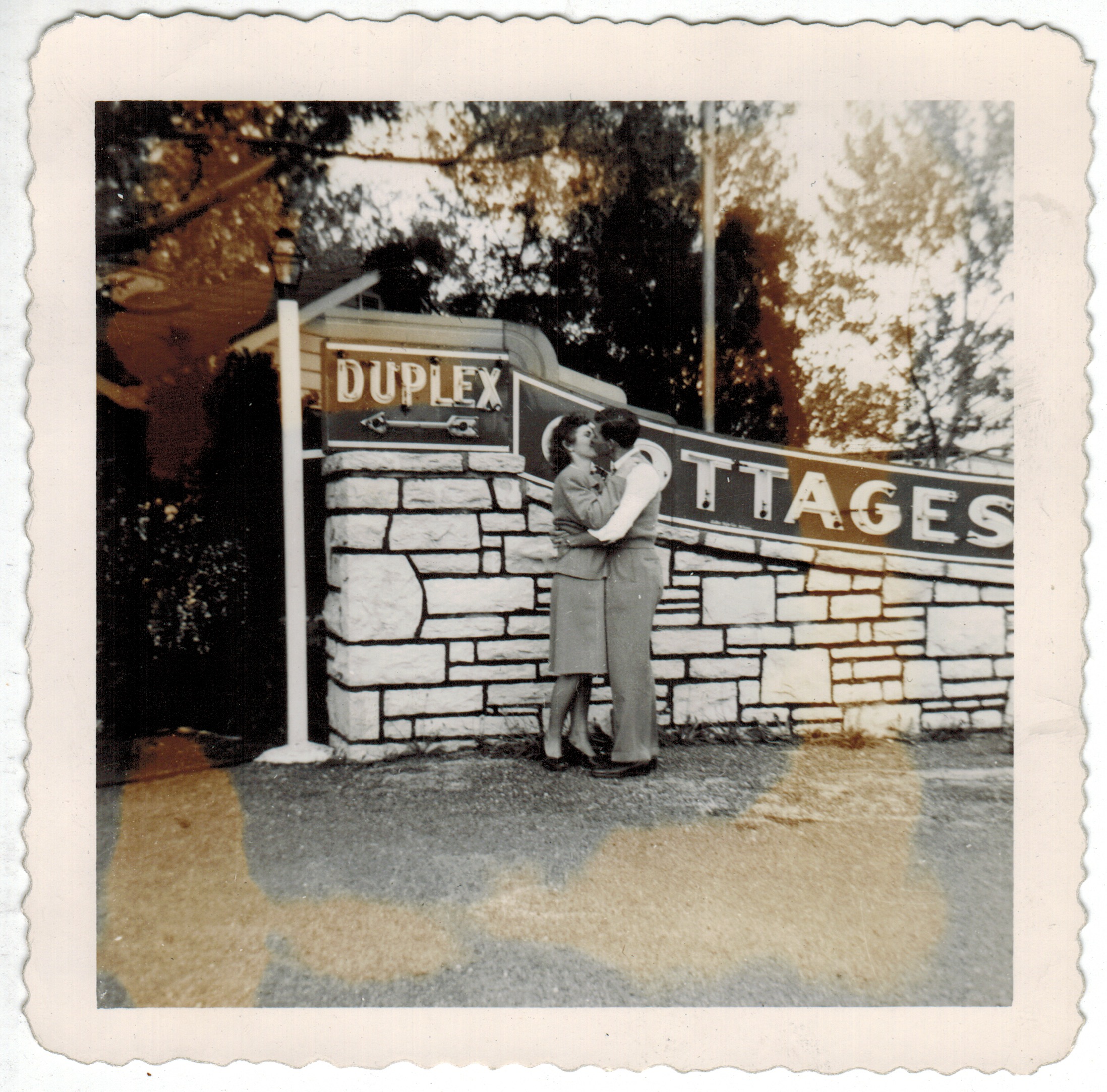

The couple at right are locked in an intimate embrace in front of a neon sign indicating they’re at a motel — for the night! This is not just a date, it’s an elopement or a wedding. And they’re celebrating that at a roadside motel, perhaps as part of a road-trip honeymoon to visit important American landmarks. The photo, taken with the neon sign as symbol of what happened that night, will fix this trip in their past, as well as in their future.

Scroll down for more examples of my research in and with different communities.

Photograph: Collection of Dydia DeLyser

DYDIA DELYSER: LIVING GEOGRAPHY

Collecting, preserving, and restoring—intervening to share the past with the future

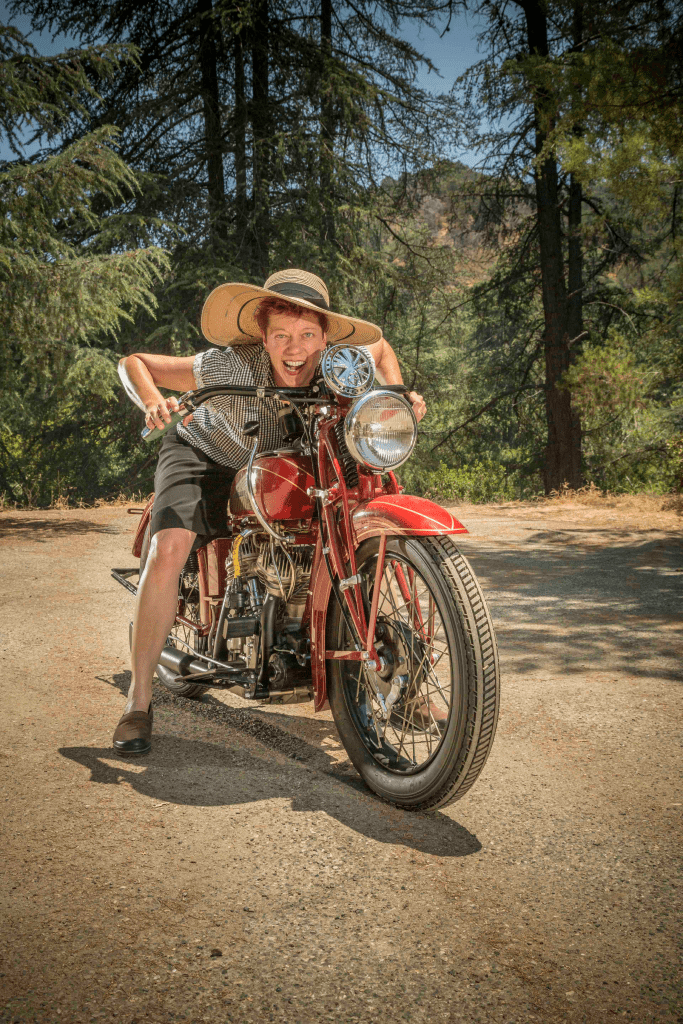

Many things slip through the cracks of ordinary archives and mainstream museum collections. Often these are things taken for granted, objects used in everyday life, things not yet considered antique, and perhaps even objects deemed unworthy of attention. My research values such objects by collecting, preserving, and restoring them myself—and then using them in my research, living with them in my life, and sharing them with the public.

For example, though historic traces are known to favor people in positions of power and wealth, my research has sought to bring to light traces of the lives of people more ordinary. Like tourists. Building an extensive collection of historic tourist souvenirs related to the 1884 novel Ramona (below) has enabled me to shed light on how the novel became meaningful in the lives of people now dead, at tourist attractions now extinct.

Souvenirs are difficult to study because, once they are purchased, they become geographically dispersed. Yet many of us buy, give, and live with souvenirs of all kinds. Once those souvenirs arrive home we often use them along with other objects of everyday life, yet they always retain the imprint and the memory of the place from which they came.

At left, a small portion of my collection of ornate sterling silver souvenir teaspoons, all related to “Ramona’s Marriage Place,” one of the most popular tourist attractions in southern California in the early-twentieth century. All are different, and some are personalized with dates and initials, commemorating a journey to a place made familiar in fiction, and made real in the landscape.

Below, the “curio shop” at Ramona’s Marriage Place sold an unimaginable array of souvenirs. The photo shows a small fraction of my collection, and I’m still buying more anytime I can find them. Many are joyfully ridiculous, as souvenirs often are.

See items from my collection on display in San Diego’s Old Town State Historic Park at Casa de Estudillo in a permanent exhibit entitled “The Novel that Saved This House,” and, until June 2025, at Los Angeles’s Autry Museum of the American West’s in a temporary exhibit entitled “Reclaiming El Camino: Native Resistance in the Missions and Beyond.”

Scroll down for more examples of things I collect, preserve and restore.

Objects at left and below: Collection of Dydia DeLyser

DYDIA DELYSER: LIVING GEOGRAPHY

Not all artifacts of the past survive into the present unscathed by their life experiences. Most see age and wear. And they will need maintenance and repair. To be able to use them for their original purposes, in the present and in the future, they may even need restoration—they may need to be returned to their original state by active intervention.